by Dilshan Harischandra

The short answer would be no, they are not the same. Parkinsonism is a generic descriptive term encompassing neurological diseases whose underlying neuropathologies are clinically manifested as Parkinson’s-like symptoms, including Parkinson’s disease (PD). These symptoms include slowing of movement, tremor, rigidity or stiffness and balance issues. As a clinical syndrome, Parkinsonism also includes many atypical variants, often known as “Parkinson’s Plus Syndromes” and any other brain disease that resemble Parkinson’s, such as manganism, hydrocephalus or drug-induced Parkinsonism. However, despite the clinical diagnosis, all cases of Parkinsonism share a disturbance in the dopamine neurotransmitter system of the basal ganglia – a part of the brain that controls movement.

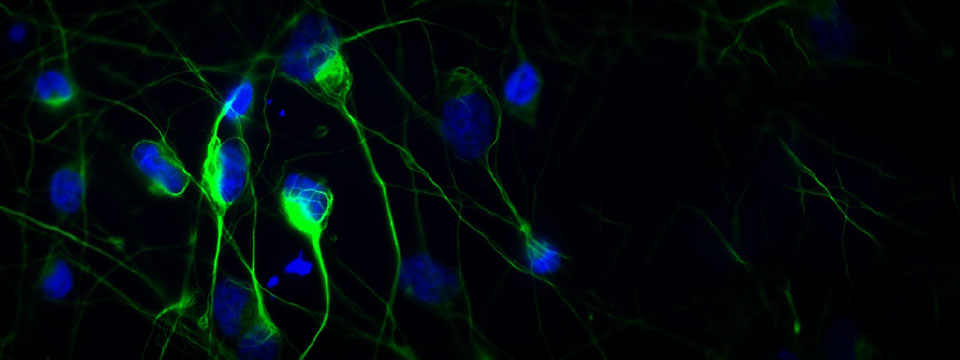

Classical PD makes up approximately 80% of all cases and arguably is the most studied form of Parkinsonism. PD is mainly characterized by selective neurodegeneration of dopamine- producing cells in the substantia nigral region of the brain, resulting in a deficiency in the key neurotransmitter dopamine. Supplementing patients with L-dopa, a precursor of dopamine, helps alleviate the shortage of dopamine and the resulting symptoms. Also, in a majority of typical PD patients, neurons in the affected regions of the brain contain Lewy bodies, which consist of a misfolded form of the protein α-synuclein. Although the exact function of this protein has yet to be elucidated, α-synuclein has long been implicated in the pathogenesis of PD.

The remaining spectrum of Parkinsonism comprises rare, severe neurodegenerative disorders including progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Lewy body dementia (LBD) and multiple system atrophy (MSA, also known as Shy-Drager syndrome). Besides sharing similar symptoms with typical PD, these movement disorders are distinguished by their own unique symptomology. For example, in MSA, aggregated α-synuclein depositions are seen in the brain’s glial cells instead of in the neurons; and in PSP and CBD, an abnormal accumulation of “tau” protein, which normally binds and stabilizes microtubules within cells, is observed instead of the accumulation of α-synuclein seen in classical PD. Another classic example is LBD, one of the most common causes of dementia in the elderly population. While LBD patients likewise accumulate an abnormal aggregation of α-synuclein in their brains, they also suffer from visual hallucinations, which is non- existent in typical PD patients. Clearly, even though Parkinsonism comprises disorders having many overlapping symptoms, signifying altered dopamine neurons, the diverse array of distinctive symptoms and underlying neuropathologies makes diagnosis and development of effective therapeutic agents to battle this spectrum of diseases that much more difficult.

Our research in Dr. Kanthasamy’s lab focuses on unraveling the cellular and molecular mechanism of Parkinson’s disease and other protein-misfolding diseases. Our lab uses multidisciplinary approaches to understand cellular signaling mechanisms that regulate the survival of dopamine- producing nerve cells and to try to develop novel translational approaches to slow down the progression of PD. We are also interested in understanding the role of environmental neurotoxic chemicals and other neurotoxic stresses on PD pathogenesis. In recent years, we have made several advancements in understanding how occupational neurotoxicants interact with proteins to mediate neuronal cell death processes. Our lab has also made several fundamentals advancements in elucidating the role of protein kinases such as PKCδ and Fyn kinase in regulating dopaminergic degeneration in animal models of PD. With strong financial support from the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Kanthasamy is able to mentor many graduate students and to adopt many state-of-the-art tools and techniques so vital to overcoming barriers to filling the existing gaps in knowledge.