and the Power of Suggestion

On January 17, 1995, an earthquake measuring 6.9 on the Richter scale hit the island of Japan. The epicenter was located 40 miles from Kobe. It was the worst earthquake in Japan since 1923.

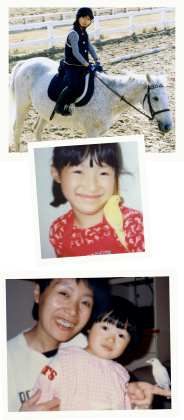

Born in Osaka, Japan, Dr. Yuko Sato was nine years old when the 1995 earthquake hit. Osaka, located 18 miles from Kobe, was impacted. “Everyone was in shock,” said Sato, poultry extension veterinarian at Iowa State University. “As therapy my dad took me to a facility where I could ride horses. I thought that was pretty cool and riding became my hobby.” For Sato, the horse riding helped regain a sense of normalcy. More surprisingly, it would be the initial catalyst for a career path she never imagined.

Parental Influence

“In Japan, the educational system values uniformity,” Sato said. “My parents, though, were progressive thinkers who wanted me to be unique and make a difference. They knew the key to my success would be to be bilingual, and to continue my education, beyond the Japanese K-12 system.”

Sato went to Catholic school in Japan for 14 years, pre-school through high school. When she was 16, her parents sent her to summer school at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she completed two semesters of coursework. At 17, she spent six weeks in class at UC, Davis.

When it was time for Sato to look for a college, she narrowed the field to U.S. colleges with equestrian teams so she could continue to ride horses. Ultimately she decided on Berry College in Rome, Georgia.

Power of Suggestion

Sato was on the wait-list for a job at the college’s horse farm, when her undergraduate advisor got her a job at the dairy barn. It was during that work experience when her advisor told Sato that she had enough credits to go to veterinary school. “It never occurred to me to become a veterinarian until my advisor suggested it. I’m an only child so my plan was to major in business and eventually take over my parents’ business. But I grew up in the city and was fascinated with agriculture so I pursued a degree in agricultural business.”

Sato entered veterinary college at Purdue University in 2008, and tracked food animal medicine with a focus on dairy medicine. During Sato’s fourth year of veterinary school, with graduation looming close, the job outlook wasn’t good. “It was 2012, and the economy had not rebounded from the Great Recession. I was going on a lot of job interviews.”

Sato was relaxing at her apartment pool, when her classmate, Dr. Dan Wilson, suggested that Sato look into a poultry residency program one of their professors, Dr. Pat Wakenell, was developing. “The program was not even approved yet, but Dan told Dr. Wakenell that I was interested.” Sato hadn’t considered poultry medicine, but was intrigued because of the consulting and business aspect of the field. “My dad does consulting, and I was always attracted to the idea of helping a company do better.”

Soon after that poolside chat, Sato interviewed with Wakenell for the residency position. A few weeks later, Sato got a telephone call from Wakenell offering her the residency.

“I was excited,” Sato said. “Dr. Wakenell took a gamble with me since I had no previous experience in poultry. She relied on my classmate’s recommendation, along with a couple of others. Now, because of her, I had a career path in poultry medicine.”

Right Place, Right Time

After completing her residency and receiving a master’s degree, Sato came to Iowa State in August 2015. When she arrived on campus, Iowa State was playing a significant role in the response to the outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza. She would serve in a critical role.

As the university’s poultry extension veterinarian, Sato was busy working with state and federal officials, as well as answering questions from poultry owners with flocks of all sizes, serving those with large operations as well as owners of backyard chickens with a name.

“The outbreak allowed me to connect with a lot of people in Iowa, much more quickly than normal circumstances would allow,” Sato said.

Now, Sato spends part of her time teaching poultry classes to undergraduate and veterinary students. To meet a growing interest in poultry medicine, Sato developed a clinical rotation for fourth-year veterinary students. “During the two week-rotation, the students travel to poultry and turkey operations in Iowa and Minnesota, gaining experience in a variety of flock sizes and management systems.”

Sato also helps poultry producers develop successful animal disease management programs, focusing on early detection and prevention. Sato preaches biosecurity at the farm level. “We want producers to make it difficult for pathogens to get on their farm.”

In helping producers prepare for any future animal disease threat, Sato is making her mark on the nation’s poultry industry. It’s a long way from where a young Sato envisioned her future, but a career path that challenges her to be an agent of change.

Dr. Yuko Sato is an assistant professor in the Department of Veterinary Diagnostic and Production Animal Medicine. She is also board-certified by the American College of Poultry Veterinarians.

November 2016