It seems out of place. Why would a portrait of President Theodore Roosevelt be hanging on a wall in a scientific laboratory in the College of Veterinary Medicine?

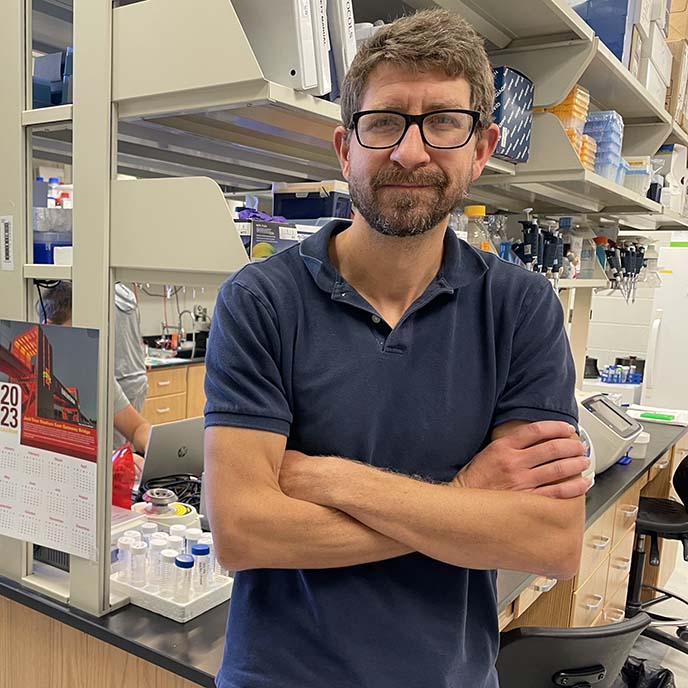

It turns out to be fitting that “TR” holds a place of honor in the lab of Dr. Josh Beck, assistant professor of biomedical sciences.

The microbiologist and his lab conduct research on Plasmodium falciparum, the parasite that causes malaria, a serious and sometimes fatal disease that causes people to get very sick with high fevers, chills, and flu-like illness.

The connection? Roosevelt, who served as the 26th President of the United States, came down with malaria while in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Years later, while on a hazardous journey down the Amazon in South America, Roosevelt contracted a tropical fever that resembled malaria.

“Roosevelt’s tenacity of spirit makes him a good mascot for basic science, which involves a lot of troubleshooting and failure,” said Beck, an admirer of the former president and naturalist. “The discovery process is enormously rewarding, but you have to be tough.” Roosevelt explored the Amazon in 1913 when malaria was a significant health issue in the United States. It remained that way until the early 1950s.

“As a result of measures that controlled the mosquito vector and reduced parasite transmission, malaria is no longer a significant health problem in this country,” Beck said. “There hasn’t been a locally transmitted case of malaria here for the last 20 years, although thousands of U.S. residents still contract the disease each year while traveling to endemic areas.”

That is until this summer. Nine cases have been reported in the southern U.S. and Maryland, causing a wave of concern among the medical profession and interest among researchers like Beck.

“Local transmission is not a major concern at this point,” Beck said, “but health care providers should be aware of these new cases and consider a test for malaria, when warranted by the symptoms.”

Malaria is a serious issue outside the United States. Worldwide, more than 240 million infections are recorded annually. Approximately 600,000 people, mainly young children in Sub-Saharan Africa die each year from malaria.

It’s one of the reasons why Beck, a microbiologist by training, is studying the disease. While at Iowa State he has initiated work with the mosquito vector, allowing his group to explore protein export by the malaria parasite during its initial infection of the vertebrate host liver. This is the starting point of the disease which has emerged as a key vaccine and therapeutic target.

Beck’s work is supported by the National Institutes of Health.

“We want to understand how the parasite takes over its host cell so we can develop new therapeutics and vaccines that target these processes,” Beck said. “That’s what motivates what we are doing here.”

Beck has traveled to East Africa and met with people who have contracted malaria. Those experiences, like the one Theodore Roosevelt endured in the Amazon over 100 years ago, weigh on Beck’s mind.

“Malaria is a devastating disease,” he said, “and if it’s not treated it can be fatal, especially among young children.

“Developing new tools for malaria control can have a major impact on the lives of so many around the world who continue to be affected by this terrible disease.”

September 2023